Produced for The Learning Institute

Through the SEAFDEC-funded Strengthening Community Fisheries (CFi’s) Management and Livelihood Diversification in Cambodia project, The Learning Institute has helped community fisheries integrate a gender perspective and through the support provided, the Bak Amrek-Doun En CFi is now a great example of gender equality in action.

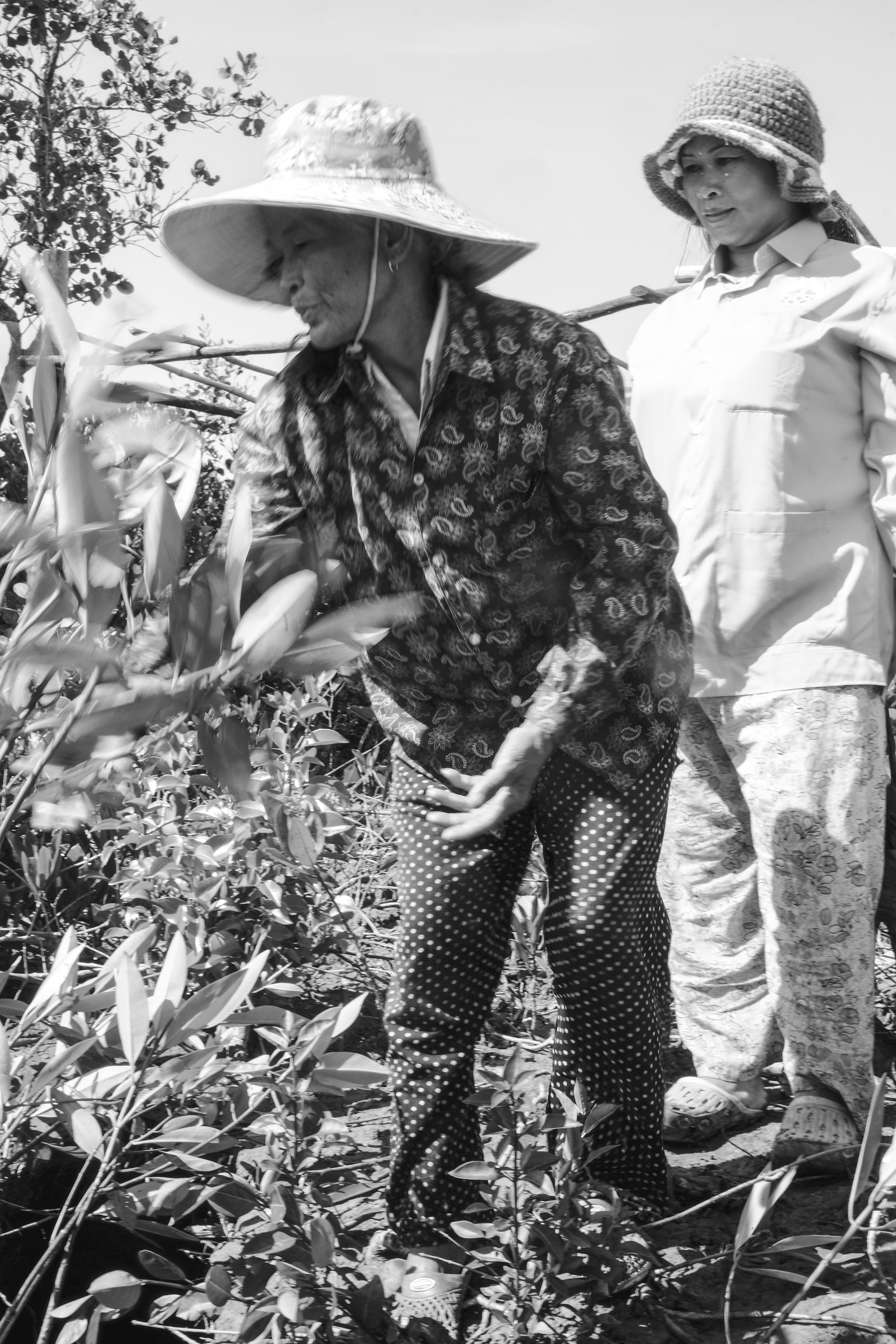

"The Women of Bak Amrek" is a short film developed by The Learning Institute during a field visit in 2017. We followed the footsteps of the community members who took us to the fish conservation zone and plantation and farming sites. We had the opportunity to have several conversations with CFi committee members and others on the matter of women’s representation and gender awareness in the community.

Strengthening Community Fisheries (CFi’s) Management and Livelihood Diversification in Cambodia had three vital objectives:

1) Strengthen the legal and constitutional rights of community members and fisher-folk around the Tonle Sap Lake and in Coastal Provinces of Cambodia through improved and diversified livelihoods options and sustainable management of CFi’s,

2) enhance the capacity of local fisher-folk, women and youth groups, community fisheries organizations in the "Coastal and Inland areas of Cambodia" including the capacity of staff of the Fisheries Administration and provincial agencies in support of sustainable fisheries and habitat management, and

3) improving the recognition of the role of women and integrate a gender perspective in the development of rural/coastal livelihoods and in community fisheries (and habitat) management.

The project was implemented in seven Community Fisheries (CFi) spread across six provinces: Kampot, Kep and Preah Sihanouk in the Coastal region and Kampong Chhnang, Pursat, and Battambang in the Tonle Sap region.

During the course of the project, a large number of activities were planned and executed and through the scoping study that was conducted in 2014 in each of the CFis, it was found that while the value of women’s participation is being noted and respected, it is rare for a woman to play a key role such as the chief of a CFi.

More often than not, women in the CFis are well known as leaders of savings groups, crab banks and fish processing groups. The challenge of CFIs in relation to women’s involvement is about the limited number of women representatives. The initial scoping mission concluded that there was a big gap that needed to be filled for better management of fisheries using gender approaches (2013-2015 Report).

While there were some gender-specified activities planned, it was decided that the integration of a gender perspective in the Community Fisheries could be best applied if it was implemented as part of the other activities.

The gender awareness and best practices training was conducted April to May in 2015 and March to April in 2016.

These two-day training courses were conducted in the CFis and were participated in by the CFi members, community members and also the local authorities. CFi’s from Kep and Kampot were not targeted as a part of this training as they had previously received gender training through another project with the Learning Institute.

This training module covered points such as the definition and distinction between gender and sex, gender roles, gender equity and equality, gender bias and implicating the role of women in CFi management. A Gender Concept Module (Training Manual on Gender Foundation in Fishery Community Management) was later develop for use as additional material while conducting other activities to introduce the concept of gender as it was found during the training module that the distinction between gender and sex wasn’t always clear.

During the 2014 scoping mission, The Learning Institute found that the Anlung Reang CFi (Pursat Province) and the Sdey Krom Rohal Soung CFi (Battambang Province) were rare cases in comparison to the others as there already was a high rate of engagement from the women hence achieving a large number of accomplishments not just in CFi management but also other livelihood interventions (2013-2015 Report).

In due course, the Bak Amrek Doun-En CFi (Battambang Province) has also proven to be a success in integrating women into their CFi management as well as livelihood interventions.

Through this project, The Learning Institute has also been able to assist in reviving the women’s savings group in Bak Amrek Doun-En and Phum Thmey CFi. While the savings groups had been created previously, they had remained inactive due to lack of interest, support and also funds. As part of a youth activity, The Learning Institute issued a grant for savings groups and they have now been given a fresh start with a mix of younger and older male and female members and has provided aid to several individuals.

Although one of the smaller CFis in size (1075 Ha), the Bak Amrek Doun-En CFi has the largest number of CFi committee with nine people of which three are female. There are also 360 CFi members where 222 are female.

The main livelihood activities in the community are fishing, farming, rearing livestock as well as some small businesses. Although they have had setbacks with a lack of community support and an inadequate number of people to crackdown on the use of illegal fishing gear, they have been very successful in setting up a conservation site that produces benefits during both the dry and rainy season. The integration of women in these communities cannot be implemented by force. It needs the involvement and participation of both men and women to introduce these changes and Bak Amrek has welcomed this.

Sou Sous, a CFi committee member in Bak Amrek Doun-En, said that unlike previous times when women didn’t have any functions in leadership roles, that has changed. Today, women are strong enough to lead. As someone who has been well-informed about the concept of gender through previous training and workshops, he also adds that while women need to be given the more central focus, gender is not only an emphasis on women but also on men.

During the conversation, it was clear to see that Mr. Sous was proud of the women in his community but more so of those CFi members with whom he works closely as these women have been quick to take the initiative and solve imminent problems they’ve faced in their fisheries conservation site.

“I DON’T KNOW ABOUT WOMEN IN OTHER COMMUNITIES, (BUT) WOMEN IN MY COMMUNITY, IF THEY NEED TO GO INTO THE LAKE TO REMOVE THE ILLEGAL EQUIPMENT’S, THEY’LL SWIM FOR IT. AND IF THEY NEED TO BURN IT, THEY DO THAT TOO”

–

SOU SOUS

Mr. Sous also talked about how the inclusion of women in the patrolling groups are an asset. He gave us an example of the illegal fishers; that offenders include both men and women.

As men, when they go to confront them and put a stop to it, either the men get violent or the women start appealing to them and in both cases, they feel handicapped. But with women now included in the group, they can help diffuse the violence as well as talk directly to the women and this results in them being able to confiscate the illegal gear.

Mr. Sous adds that the end of the Learning Institute’s project in their community will not be a barrier to women’s empowerment because their CFi committee will continue to choose women to be in the committee as leaders and also that they will try to provide training in nearby villages and communities about gender integration as well as women’s rights.

Mrs. Khel Khem is another senior CFi committee member and a prominent member of the community who has and continues to work on behalf of the welfare of women in the community. As committee members, she feels that they (along with the other women representatives) are leaders and must support and demonstrate their capabilities for other women in the community.

Like Mr. Sous, she is also determined about continuing to promote gender awareness once the project with The Learning Institute phases out. She says that the committee members will continue to support women and other community-related projects because this will ensure that the community is protected and will also give the people a form of livelihood, no matter how small it may be because “if not, we will fail when the project finishes”.

As this four-year project comes to an end, the response from CFi community members and representatives about the recognition of women and integrating a gender perspective in the management of Community Fisheries is hopeful and positive.

Bak Amrek Doun-En is just one the examples where the inclusion and leadership of women has exemplified a change for the better and it is the hope of The Learning Institute that these communities will not only continue to transform but also serve as blueprints for other Community Fisheries to be more inclusive and challenge the gender barrier.

Interviews conducted for this story were translated from Khmer to English by Kong Phidor